The clue is in the name – an aspect is an aspect of your character that you want to be important, and be recognised by others as important to your story.

An aspect is anything about your character that is not a skill or supernatural ability. Are you fast, double-jointed, charming, a womaniser, in debt to a crime lord, or even are you an actual crime lord?

Han Solo, for example, might have Swashbuckling Smuggler, Debt to Jabba The Hut, I’ve Got a Bad Feeling About This, Chewbacca (Strong Mechanic Sidekick), The Millenium Falcon.

In one game, he might have a different set of aspects – it all depends on how the game is constructed and what aspects of the character the player wants to shine a spotlight on.

You can design a character without understanding anything about aspects – just go with your gut and everything will work out.

How Many Aspects?

You have five Aspects. There are ways to get more, but five is the standard. They start out as your Heroic Archetype, an Eldritch Mystery, your Tragic Flaw, and two Supporting aspects.

When designing characters, those first three need to be defined, while the last two can be left blank and added when inspiration strikes (or when you first need an aspect).

There are rules below on how to choose your aspects. Don’t agonise too much – they can change during play, you aren’t stuck with your initial decisions.

What Bonus Does an Aspect Give?

The primary benefit from an aspect is how much does it alter a roll. This isn’t the only benefit, but it is a very important one.

When you make a roll, you might get a Poor, Fair, Good, Great, or even better result. Aspects modify the rank you achieve. They might add +1, +2, +3, +4, or a random 1d6 bonus. In this system, a +1 bonus is a big bonus, but aspects are limited so typically give an even bigger bonus.

Players make a lot of rolls so will get a few bad rolls they really want to avoid. If they can explain how one of their aspects fits the situation, and describe what that looks like, the aspect can alter the outcome.

The GM shouldn’t worry too much about why the player can use the aspect – players only have a limited number of uses and quickly run out if they use them too frivolously. It’s not the GM’s judge to decide if an aspect fits the situation – that’s up to the player.

What should matter to the GM: how the aspect applies – how it is narrated. It’s really important that the aspect be demonstrated, not simply, “I’ll use this aspect and get +2 (or whatever).”

Say, Greg’s character has the Strength of a Giant, and Greg rolls badly when trying to kick down the door during a heroic escape. Greg looks at the result, then describes his characters muscles tensing, and the door creaking as it is torn down. That sounds a reasonable use of the aspect, and is very noticeable to any witnesses helping to define the character’s image and personality, so the GM nods and goes with it.

Later, Emily’s character is arguing with the magistrate, and rolls badly. She says she’ll spend an aspect and make that roll succeed. The GM asks what that looks like. Emily thinks for a moment, notices her character has an aspect of Haughty and Belligerent, and says that Emily’s character talks down to the magistrate, how dare he think he can tell her what to do, doesn’t he know who she is? The GM agrees this sounds perfect for her, and displays her personality memorably, so the aspect is used.

How and When Do Aspects Recover?

As described in the post about Stress and Conditions, play time is divided into scenes (bits of a session), chapters (entire adventures) and advances (the time it takes to get enough experience to advance noticeably – typically 2-3 sessions, less if the sessions are long).

You recover all aspects at the end of each Chapter, and when a Compel is offered and acted on (see below). The GM might let you recover ONE aspect at certain times, but this shouldn’t be relied on.

Gaining Aspects

You can gain bonus aspects through the Knack system. Even if you don’t add extra aspects, you can swap one aspect for another, or redefine existing ones, In this wy a character can evolve.

When you gain a new Aspect, try to tie it into the situations in the game you are playing. A character who spends a lot of time hobnobbing with their peers might now be Putting on Airs, or have High Status Contacts. You have a lot of flexibility, but the new aspects must be okayed by the GM and accepted by the other players – so they have to make sense.

Tagging an Aspect

Aspects are lasting (if not permanent) aspects of your character, and they are always true. So if you have the aspect, The Best Arm Wrestler In The World, you are always the best arm wrestler in the world. When in a situation that calls for arm wrestling, the GM should use this aspect to set the difficulty, and you might not need to roll at all.

Note to GM: generally avoid aspects that suggest the player is the best in the world at something. You might want to introduce an NPC who challenges them or is better. But it’s appropriate for some games.

Whenever the aspect grants a benefit because you have the aspect, that’s tagging an aspect. This might make task rolls irrelevant, but doesn’t affect conflicts.

The GM should think carefully before accepting aspects that undermine a character’s roll in adventures or which clash with skills. Having The Best Fencer In The World might make Ferocity rolls less important – then again, maybe it won’t. You can be a great fencer who just isn’t great at fighting: but you might need to explain why. Maybe you focus on sports and instruction, and lack the ruthlessness needed to be a good killer.

Invoking an Aspect

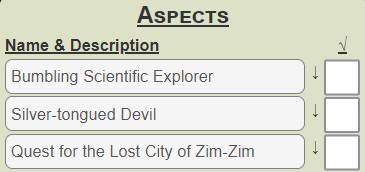

This is the real reason you have aspects. A certain number of times each chapter, an aspect provides a huge bonus to Ability rolls. For simplicity, you have a list of aspects, each with a checkbox, but any checkbox can be used for any aspect.

This character might use all three boxes here for Silver-Tongued Devil.

Generally speaking, you can’t use an aspect more than once in a Scene, but can Invoke others. Over the curse of a Chapter, it’s easy to imagine the same aspect might be used many times. It’s okay to have aspects that you can’t imagine using very often – they tell us something important about your character, and that box can be used for other aspects. The ‘balance’ is provided in the total number of boxes.

The Invoke Benefit

In some games, an aspect provides a small (but still significant) bonus on skills and in others it is overwhelming. This is a dial the GM can set when creating their game. Typically, they provide a bonus of 1d6, but it can be a fixed bonus from +1 to +4, with an average of +2. Remember in this game, even a +1 is a big bonus.

You see the roll before adding the aspect, so you’ll usually be able to tell if it is going to make a difference. An aspect should matter, and is never wasted. So, if you use an aspect and it doesn’t change anything, you get that spent aspect back.

When you get a bonus, you can’t raise a roll above Spectacular – the only rank above that is Legendary, and that is reserved for special rolls (critical hits).

Invoking For Narrative Effect

Sometimes, the GM might set an aspect as a cost, “that’ll cost you an aspect.” In this way, aspects represent a player’s ability to influence the narrative. Say they are fighting in a castle, and a player asks, “Are their weapons hanging up on the all?” The player knows they can use them if there are. The GM knows that too, and says, “Sure, but it’s not common so that’ll cost you an aspect.”

Likewise, the player might say, “I have Lover in every port” – is there someone in this port town I can call on for help right now?” The GM thinks that makes sense given the aspect, and says, “okay, check the aspect, and it is so” (or the GM might ask what sort of help the player wants before deciding if there is a cost).

Remember, “Check the aspect,” has the same meaning as, “Check any aspect.”

The Limited Use of Aspects

Some players have difficulty coping with the idea of aspects that apply some but not all of the time. If you have Strength of a Giant, shouldn’t that apply in every situation where strength matters?

But aspects in this situation are about spotlight. They are not physics, they are drama. Think of a movie, and when the camera and plot decide to highlight a character’s special strength or charm or whatever. That’s what aspects are: they allow you, the player, to decide when you have the opportunity to say this roll matters, and then you invoke an aspect and make sure it does matter.

Aspects as Limited Powers

Sometimes it makes sense to use an aspect like a power. This is most common with the Eldritch Mystery aspects – that’s part of the reason they are there.

Decide if the benefit fits a Tag, Invoke, or Narrative Effect. (It’ll often be a Narrative Effect.) When using an aspect in this way, you always get exactly the same benefit as any other aspect (not a Power), but it allows aspects to be more flexible.

Compelling an Aspect

A Compel means something happens that creates a problem for you, or showcases your less-heroic side. Compels are initiated by the GM, and usually are about something happening in the world for you to react to.

Palominus has the Aspect: Never backs Down, and the GM says, “the ruffian puts a gun to the prisoner’s head, and says, “Walk away, let me take the treasure, and she lives.” What do you do?

A compel should be a call to action – it provokes a character into taking action, or presents a dilemma the player must react to.

Palominus has the aspect, Code of Chivalry, and is standing guard over the witness to a series of murders. While he stands guard, he sees across the street a group of bullies dragging a weaker victim into an alley. “Do you rush to his rescue?”

The player knows she can accept the compel and rush to rescue, and get an in-game reward. But if she does that, she also knows the GM will do something to the witness – thats what the Compel is for. So does the player want to let that happen to showcase their code of honour?

Accepting a Compel

When you accept a Compel two things happen:

- Immediately recover all used aspects. That’s a big benefit, even if you just recover one!

- The very first roll related to the Compel gets a bonus – treat it as if an Aspect was spent on that roll, for free. You really do showcase that aspect. (If it’s a conflict turn, apply to all rolls in that first turn.)

Each compel is also often an opportunity (but this is not required).

Palominus’s first blow downs the leader of the bullies, and the rest flee. The rescued victim turns out to be the son of a local aristocrat, and will remember this rescue. This may come into play later. Palominus returns to the witness- and find the apartment broken into, and the witness gone!

Refusing a Compel

Whenever you refuse a compel, the situation does not happen. The GM must have declared this is a Compel or communicated this understanding somehow, and you know you probably won’t be offered another this session.

Palominus is guarding the witness, and the GM describes the bullies grabbing their victim and dragging him into the alley. The GM states, “Your Code of Honour is compelled.”

The player states, “Nah, the witness is too important to me. I refuse the compel.”

The GM states, “Okay, forget the bullies. That didn’t happen. You night of guard-duty is uneventful.”

This rule is important – it means that the player isn’t repeatedly being put into situations where they are incentivised to act against their Aspect.

How Often to Compel?

The GM should try to inflict a Compel on each character, once per session (unil the Compel box is checked for this Chapter). The player can accept or refuse the compel.

Whether to accept or deny a compel is always a player choice – not a character choice.

This should be something the GM strives for, but don’t agonise too much if you cant. This is partly a player responsibility – pick aspects where it’s easy to imagine how they are compelled!

A player might not want to be influenced by the GM, and choose Aspects that just don’t make for good compels. That is okay! Players always have their own agency.

Minor Compels

The GM might offer minor compels here and there, especially if your character is easy to compel. A minor compel is something which causes you to fail a single roll, and may create a complication on that roll. You get one aspect back for accepting this compel.

There is no recorded limit for how many minor compels can happen, though individual GMs might create their own limits. Some GMs may never offer any.

Players can suggest compels when it fits their character and their aspects, in the hope of getting one. The GM might agree! If the entire group think it’s appropriate, the GM probably should too.

Concessions

Once per chapter, each player can decide their character is defeated, and they describe how that defeat happens.

The character is removed safely from the scene. They cannot affect its outcome in any way – they are gone. The player decides exactly how that happens. Ideally, the player should tie it into one of their aspects, or a facet of the current conflict or situation.

Lisa knows that her character, Conrie, is going to be defeated, but they have been fighting in these crumbling catacombs. Her player suggests she the there is an underground river, the floor collapses beneath Conrie plunging him into the water, and he is speedily swept away. When he recovers his bearings and gets out of the water, this conflict is over. The GM agrees that sounds good and says it is a valid Concession.

The player describes how they start the next Scene (with GM approval). If the GM thinks this gives some unusually good narrative benefit, they might assess an extra cost in aspects.

NPC Concessions

Generally speaking, NPCs cannot concede. This is a PC benefit. But if the GM wants a concession-like effect, they can suggest it to the PCs, and if every PC accepts, they recover one aspect and the Concession happens.

The players are beating up Baron Plaine and his minions. The GM says, “I’d like Plaine to return, maybe become a recurring villain, can I say he escapes, being driven away by the PCs?” The PCs like the sound of that, and also the idea of farming the baron for extra Aspects, so they agree.

If an NPC escapes under their own power, this isn’t granted. But if a conflict has a foregone conclusion, the GM may suggest their own conclusion for the scene, and if the PCs accept, it is treated as this kind of Concession (don’t forget the bonus aspect!).

Final Notes

With the way Aspects work, even something that looks like a drawback can often be an advantage, and the best aspects are those who you can easily imagine using to your advantage and apparently also being a drawback.

About the dF System

The text so far assumes you will be rolling the 2d6 resolution method (1d6-1d6). It is also possible to use 4dF. When doing this, aspects don’t give a flat benefit. They flip a number of dice to + values equal to half the bonus. So, if you have +2, the benefit is to flip one dice to +.

This method has diminishing returns (sometimes it grants no benefit it all, or less than the theoretical benefit, but really bad rolls always get the full benefit).

A +1 bonus does add exactly +1, and cannot be combined with other bonuses.